Startup Opportunities in Spatial Computing

A brief history and promising future of personal XR.

Every June tech bros, pension portfolio managers and Twitter threadbois the world over turn their eyes to Santa Clara as Apple hosts its annual Worldwide Developer Conference (WWDC, or ‘dub-dub’).

Among other things, dub-dub is best known as being the birthing ground of almost all of Apple’s suite of ubiquitous consumer technology. The original iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch and Apple TV and subsequent upgrades have all been launched at the event.

This year, this unmatched stable of consumer devices is joined by an entirely new product for the first time since 2015. That new product is the VisionPro.

There is nothing I can tell you about the VisionPro or Apple’s vision for the future of extended reality that a quick browse of Twitter, LinkedIn or the internet at large cannot. The point of this article is instead to try and observe 1) how we got here; 2) why people are building computers for your face and 3) the many divergent paths this may lead us.

XR: A Brief History

For the uninitiated, XR refers to extended reality - a catch-all blend of augmented reality (AR, e.g Pokemon Go), virtual reality (VR, e.g Oculus Rift) and ‘capital R’ Reality (e.g. Google Street View). Mixed reality is another term that exists largely on the same dimension as AR and thus will mostly be ignored here.

The modern vision for XR begins aroundabouts 1935. This was the year in which Stanley Weinbaum published Pygmalion’s Spectacles. In this short story, protagonist Dan Burke is disillusioned with the reality in which he finds himself. To remedy this, he puts on a pair of glasses that transport him to a world of eternal youth and happiness. The only catch is that he obeys its rules (T&Cs, in modern parlance).

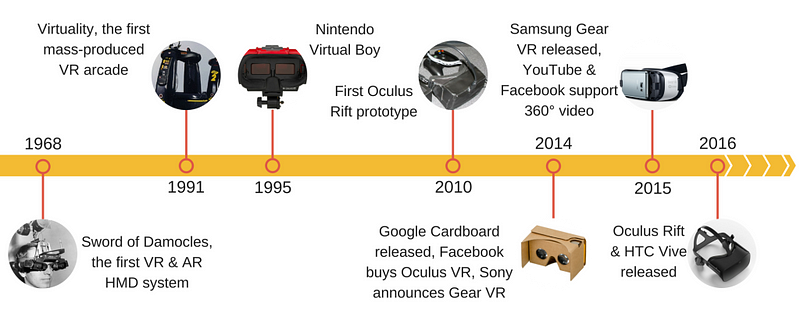

Fast forward a few decades and we begin to see the first builds of XR in real environments. This begins with Morton Heilig’s ‘Sensorama’ (excluded from timeline below), a sort of 4D cinema experience that provided the viewer with smells and a vibrating chair in addition to the sounds & sight of the film.

Also excluded from the timeline below is the first military application of XR. In 1961, Philco Headsight became the first headset with motion-tracking technology.

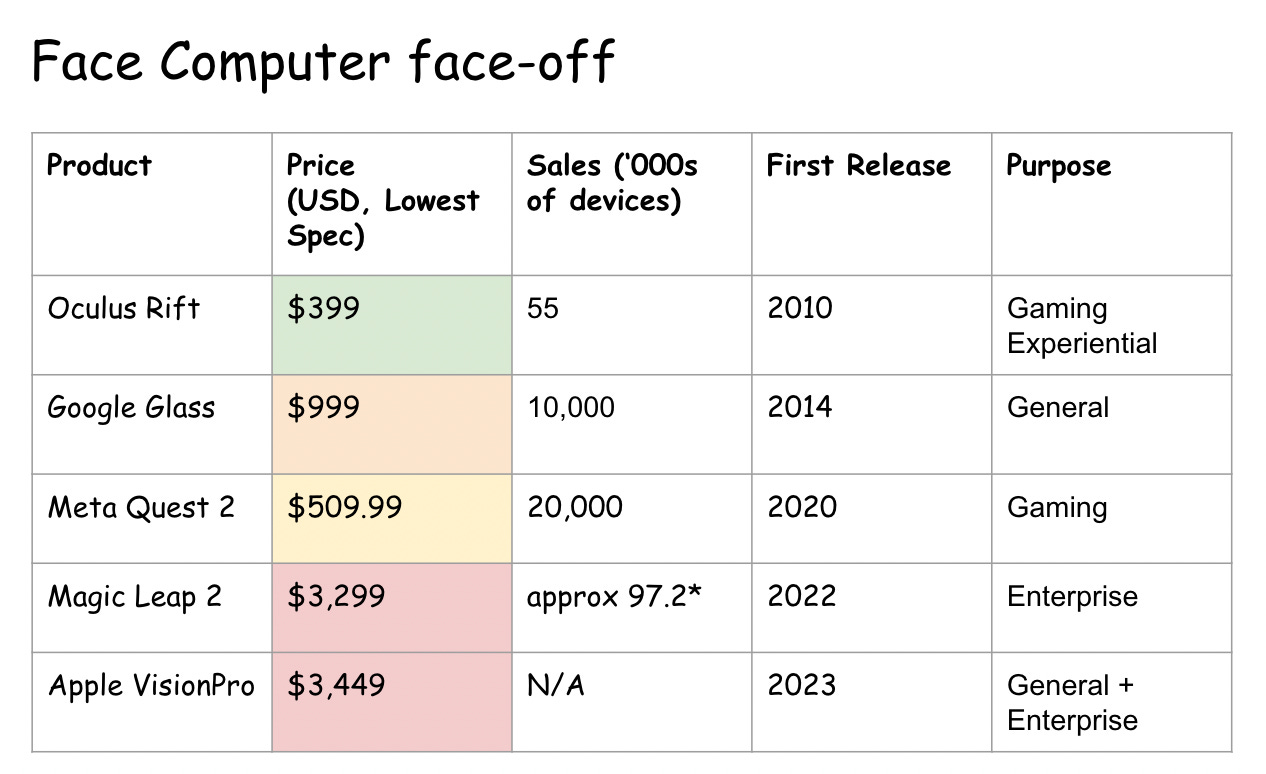

Though it has since been discontinued, the Oculus Rift was the first headset to gain real commercial appeal. Following Oculus, many of big tech’s household names joined the action. Curiously, most had different visions for who the primary customer base for these headsets would be.

The dominant expected use case for most was in immersive entertainment applications, more specifically in gaming. This was the path followed by Oculus, Sony through their PlayStation VR and Meta with the Meta Quest line of products.

Others chose to focus predominantly on enterprise. Early pioneers in this segment included HTC Vive and Magic Leap. These early movers focused their aims towards things like enterprise collaboration platforms (much like some of the metaverse plays described below), emergency response training and medical education.

Then, the metaverse hype cycle. Corporates the world over began to envision what it would look like if we took our lived environment but made it *virtual*. The vision was essentially SecondLife, but this time with less porn and more corporate work stuff.

In the wake of COVID-19, the rise of remote work created a supposed need for collaborative digital environments. Microsoft joined the party with their own industrial metaverse. Accenture launched a ‘metaverse services’ division. Facebook changed their name to Meta and begun spending $1bn per month on this vision, culminating in this brilliant presentation.

I have had fun panning the metaverse, but the hype cycle around it was an important moment in raising awareness for the arrival of what Apple would refer to this week as spatial computing. As this space evolves, there is every chance that many of these ideas come back into vogue.

Other use cases for commercial XR varied from the practical to the benign. Some of them are beginning to become commonplace in popular web back-ends. You take your pick as to which fits which description from the below:

Corporate training & education (If you’re going to watch any of these videos, do yourself a favour and make it this one)

Most of the existing devices listed above tried to achieve some sort of balance with the use cases they were targeting. The most successful to date by sales, the Meta Quest, did so by positioning hard as a gaming device.

Normally, this would be a lesson. However if anyone is to buck this trend it would be Apple. Apple has a broad suite of already ubiquitous products (1.6bn active iPhones, to name one) that can and will serve as secondary endpoints for VisionPro applications.

While Apple’s inaugural demos for the VisionPro were all hosted within working environments, it is more than likely that it will end up being a general purpose VR. I foresee its role as being a form of spatial augmentation for Apple’s existing ecosystem of products (e.g Maps, FaceTime, Siri et al) as its vision for computers shifts modalities from the . More on other potential applications later in this piece.

Headsets Today: Code New Worlds

Spatial Computing.

Rather than ride the wave of today’s tech buzzwords, Apple used their informational market making power to stamp authority on a new one at WWDC.

While it sounds intuitive enough on the surface, let’s delve a little bit deeper into what this term may actually convey going forward.

Besides the obvious branding benefits of coining a buzz phrase, the use of the term ‘computing’ feels extremely deliberate. It represents a logical next step from previous eras of ‘desktop computing’ and ‘mobile computing’. Just as Apple has done with the previous generations of personal computers, it will aim to make this concept and .

To quote Tim Cook from WWDC:

“In the future, you’ll wonder how you led your life without augmented reality”

Besides the change in hardware, where is spatial computing functionally different to its predecessors?

Arguably the most important immediate shift will be from working in 2D to working in 3D. Tasks such as visualisation, workspace navigation (i.e clicking and moving things) and collaboration will all be enabled in ways not seen under previous modalities.

In the longer term, contextual awareness and interconnectivity are more likely to prove the groundbreaking features for spatial computing.

Contextual awareness refers to the ability of the computer to i) adapt existing recommendation and notification to a user’s sensory context (i.e recommendations based on location and movement patterns, automatic changes to screen presentations based on user habits etc) and ii) provide customised (possibly agentic) assistance to users as they complete tasks in extended reality.

Interconnectivity refers to the user’s ability to extend extended reality beyond the device. Beyond just working and collaborating on holographic interfaces, users can control and interact with other devices in their environment. To take a boring example, users can change smart home settings from within the device.

In the longer run, interconnectivity may see Siri’s role as a virtual assistant evolve from voice commanded search aggregator to a living assistant that can help complete tasks from within the device based on user’s previous habits and preferences. As the baseline capabilities of autonomous agents advance, the combination of Apple’s distribution network and the familiarity of Siri may make it the killer technology for bringing personal agents to the world en masse.

Information Presentation.

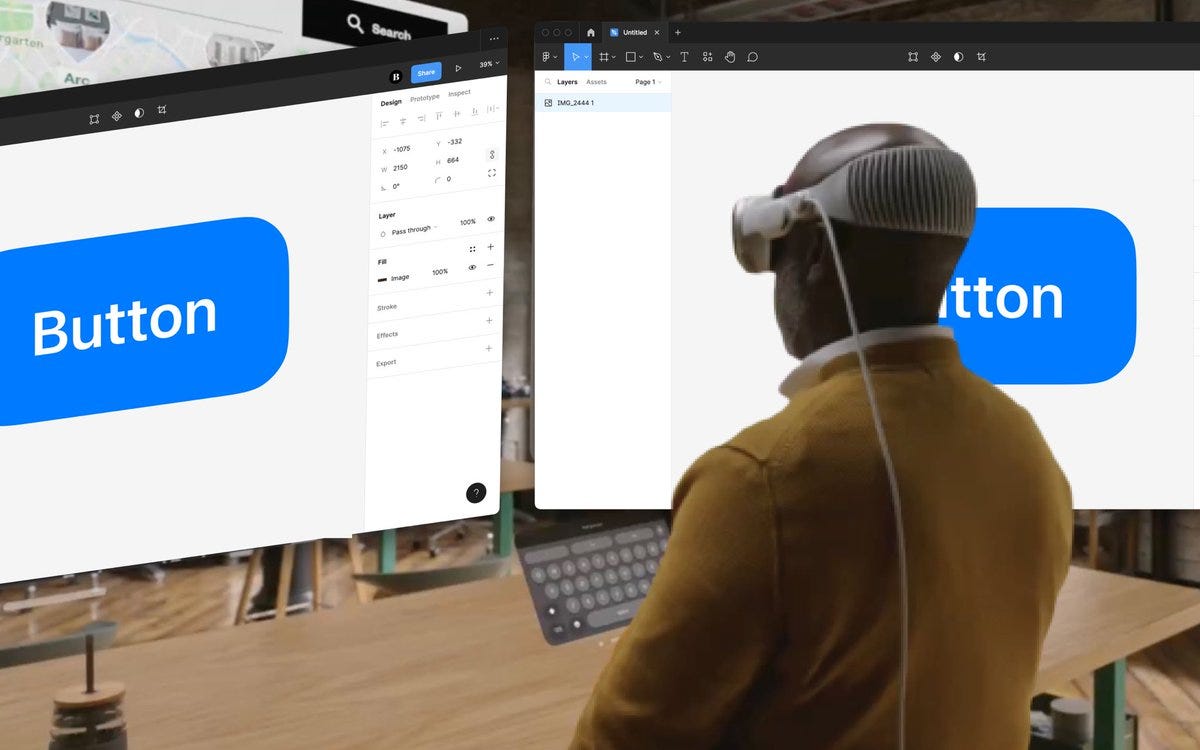

As mentioned above, Apple’s demos of the VisionPro focused almost exclusively on working environments. Make no mistake, this first generation is very much geared towards information workers. How will they use it?

Firstly, there is obvious and treaded ground. Apple will re-do and re-design all the enterprise XR solutions we have seen before. They will provide resources for institutions to train their employees, students and leaders with. They will provide the bevy of try-on solutions, gaming applications and cloud TV solutions that we have seen before.

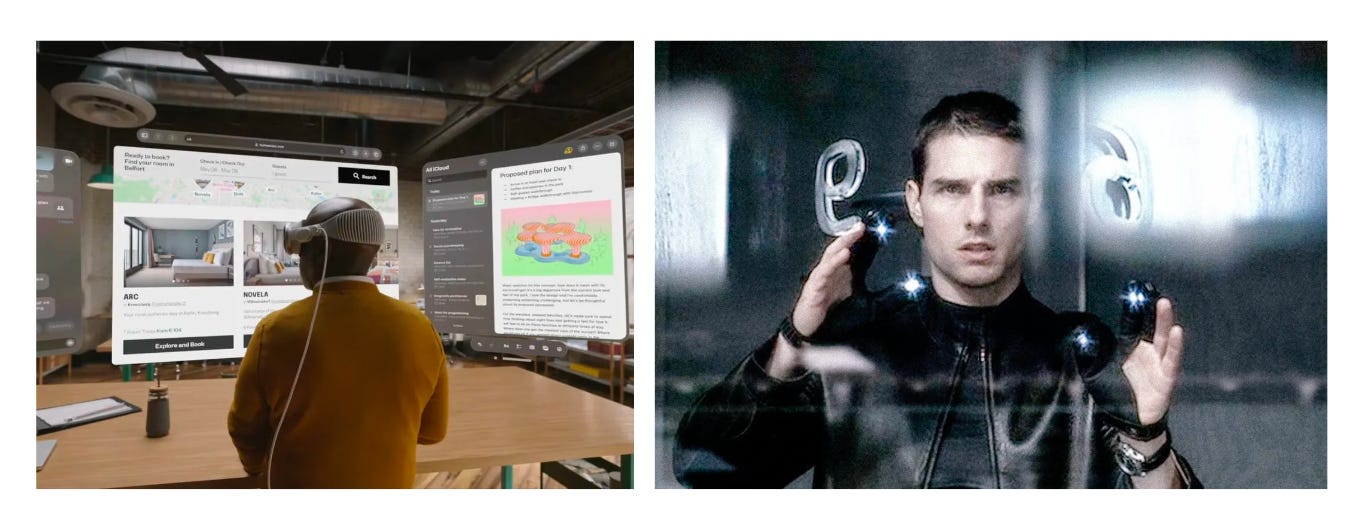

One relatively novel example that was showcased as part of the launch was ‘Minority Report’ style computer interfaces. Instead of having to boot up a physical device every time you want to work on a file, access it from anywhere in the cloud in an instant.

But how does this make the core experience of personal computing itself different?

Some early ideas:

Unlimited monitors at any given point in time

Multimodal forms of interacting with information work (speech, physical movement etc)

Intelligent browser navigation through sensory (e.g eye) tracking

Entirely custom 3D screen presentations automatically tailored to user preference

3D data visualisation (boring but important)

Each of these will present its own universe of custom ideas that will take the place of extensions and app stores before it.

AppleLM

This tweet from Cognosys AI founder Sulaiman Omar feels prescient. Apple does indeed have a history of sacrificing first-mover advantage for the sake of developing a better product over a longer timeframe. The VisionPro is a perfect example of this, being released 13 years after the first commercially available Oculus Rift.

Integrating language models into its headsets will open up a number of possibilities to Apple that aren’t available to incumbents without their own proprietary LLMs (note: Meta’s LlaMa may put them in the same boat - Balaji Srinivisan has published a great thread highlighting there potential role in the spatial computing race). Among the possibilities that this may usher in:

Virtual gaming experiences trained on users’ real-life habits.

Immediate queries through the facial ‘browser’.

Agentic virtual assistants built in to the headset and trained on user habits.

Spatial recommendation engines that recommend actions at a point in time.

Real-time translation.

Environmental augmentation allowing users to re-arrange objects in their space.

Generative content creation that plays out immediately as the user speaks it.

But could it be done more elegantly…

The Next Frontier for Spatial Computers

Many a commentator proclaimed the death of the Google Glass upon seeing it. Who would want to wear a computer on the face? Why would you opt in to looking a bit like a dork? Many have noted that not a single Apple executive even tried a VisionPro on as part of the launch.

They’re has to be a better reason for strapping one on than “because everyone else is”.

The key question in the long-run then becomes: Why would anyone want to strap an XR computer to their face when you can have one inside your brain?

The classic counter to this would be the idea of ‘reprojection’. When everyone is wearing an XR mask, we can reproject photons to make it look as though no one is. Because reprojection involves creating entirely new photons altogether, people can even make themselves look entirely different to what they actually do without the mask. This would become a killer app for catfishing.

The techno-optimist’s concept of living in augmented reality is akin to living in a perpetual lucid dream. Sleep mask when you go to bed, extended reality mask when you get out of it. Examine exhibit A below:

The current paradigm of XR relies on these exoskeletal aids for users to navigate alternative realities. The reality is that we are already so close to no longer needing to depend on these aids. Enter the brain-machine interface.

BMIs

In the long run, envisioned reality is likely to trump any form of mixed reality that exists today. I use the term envisioned reality here to describe any form of environmental alteration that is a) completely customisable to the user’s requirements or demands and b) requires no wearable aids.

The most obvious conduit for envisioned reality today are brain-machine interfaces (BMIs). For a longer primer, I cannot recommend Tim Urban’s piece on ‘Wizard hats for the brain’ from as far back as 2017.

BMIs offer many of the same ‘spatial computation’ benefits as tools like the VisionPro but without the need for strapping a weighty device to the face. Neuralink’s existing prototypes for the first commercial BMIs involve invasive implants that, understandably, make many uncomfortable (even if the reward is superhuman intelligence and memory). What about when these become less invasive, more accessible and thus more palatable to the human public?

Extended reality abounds.

Requests for Startups

Better battery systems for today’s XR devices. Mentions of batteries were oddly absent from Apple’s inaugural launch of the VisionPro. It is less obvious for ‘in the moment’ demos and usage than other design features like interfaces, compute and weight (as referenced in this thread by Kyle Samani) but equally important when used day-in-day-out.

Social infrastructure for an XR world. Not since first dates moved from cafés to online chat rooms has the core wiring of how humans interact with one another been so fundamentally rocked. How can behaviour be moderated in a world where people can make themselves appear to be anything? (note: Apple already seems to be working on some form of proof-of-identity protocol which may protect against this). What kind of content becomes more pervasive when the range of presentation methods expands so broadly? How do people come together online?

Arm the Rebels: Creative Tools for XR. SecondLife, Minecraft and Roblox all created huger than expected businesses off the back of secondary marketplaces for digital assets. These marketplaces were enabled by creative tools baked into the very fabric of the platforms themselves.

While there are many developers today already working on designs for new experiences etc for headsets and metaverse-style projects, how can we make this process more accessible for the layman (more specifically the 8-year Roblocker) to create worlds of their own imagination? What will be the second coming of Minecraft for the augmented reality or ‘envisioned reality’ paradigm?

Designs for Lived Experiences (i.e Qualia). A large part of the appeal of virtual/augmented/envisioned reality is the idea of living a different life to the one you have now. Much like Dan Burke in Pygmalion’s Spectacles, anyone will now be able to optimise their lived experiences within virtual worlds.

In the event that such technologies do become ubiquitous, this creates a giant universal market for qualia - synthetic instances of subjective experience. The design scope is theoretically infinite. How many ways can you experience pure ecstasy? Nostalgia? The pool of rewards for those who can bring these kinds of experiences to the world through some form of extended reality are enormous.

Also underappreciated may be the development of tools for users to capture or develop these qualia themselves. Is there a market for the ‘recording’ of one’s own lived experiences to share with others? How can people engineer new experiences to take to market and compose atop other open-source qualia? How can we provide guarantees of privacy for personal qualia if they begin to be used in recommendation engines?

Open-Source Hardware & XR Software Marketplaces. One thing that XR still has in common with other computing paradigms before it is its top-down nature. Users are at the whims of Apple for how they want to interact with their phones. If they want to protest this, they can select another one of the depressingly finite options on the market. To date, composability and customisability in hardware has been extremely limited.

But what if we were to open-source the development of headsets themselves through decentralised labs? Active participants could work to modify and iterate upon different hardware specifications to their preference. Modular designs could allow for customisation at the layman level. Just as importantly, these open-source labs would have no incentive to create closed loop systems for software development. Developers could experiment with, ship and deploy code that could be available to all headsets at the rate that they can build it.

Such open-source development would represent a step change in the way people interact with both software and hardware. For some inspiration, check out the great work the team at Auki Labs are already doing.

Private User Agents. Linked to the point above, the top-down software ecosystem of today means that incentives built into software tend to be warped. Rather than going all out on user utility, market incentives corner developers into building sub-optimal applications that aim to maximise metrics like ‘average session time’ or ‘clickthrough rates’.

The opportunity that open-source development studios would have to outcompete legacy tech companies by building in private, natural language user agents that act as functional assistants to their user is immense.